This observation by Henri Nouwen has increasingly become important to me. I have heard visual, musical and dance artists say much the same thing: when they reveal their most intimate truths, it touches the most people.

This observation by Henri Nouwen has increasingly become important to me. I have heard visual, musical and dance artists say much the same thing: when they reveal their most intimate truths, it touches the most people.We like to make a distinction between our private and public lives and say, “Whatever I do in my private life is nobody else’s business.” But anyone trying to live a spiritual life will soon discover that the most personal is the most universal, the most hidden is the most public, and the most solitary is the most communal. What we live in the most intimate places of our beings is not just for us but for all people. That is why our inner lives are lives for others. That is why our solitude is a gift to our community, and that is why our most secret thoughts affect our common life. (Nouwen)

During Lent, I am reading Nouwen's journal re: how he discerned his call to the Daybreak Community of L'Arche Toronto. It is candid and clarifying as I, too celebrate my deepening connection with L'Arche Ottawa. In a reflection called "Feeling the Pain," Nouwen speaks of celebrating Eucharist with the community of Trosly on Tuesday nights.

I have noticed that these people have little desire for dialogue or discussion, though they do like to pray together, sing together, be silent together, and listen together to a reflection on the Gospel. The assistants are often tired from a long day of work... and they want to be nurtured, supported, and cared for. I must learn a new style of ministry. Few of those who participate in these Tuesday night liturgies need to be convinced of the importance of the Gospels, the centrality of Jesus, or the value of the sacraments. Most have moved beyond that stage. They have discovered Christ; they have made their decision to work with the poor; they have chosen the narrow path. (The Road to Daybreak, p. 57)

Nouwen found himself gently surprised at the difference between those who gathered for worship at L'Arche, and the students and faculty he worked with at either Yale or Harvard. "I (used) to spend much energy convincing them of God's love, calling them into community and offering them a place to experience the peace of Jesus... That kind of ministry is appropriate in a secular university where students are fully caught up in the race for achievement."

These words hit me with a thundering wallop! How long and hard have I worked to encourage people in my various congregations to trust God's grace rather than their shame over perceived holy judgment? How many different ways did I pitch the idea of finding 10 minutes - 5 minutes - even 1 minute each day to bask in the light of God's love? To seek out space for silent refreshment? To let go of doing long enough to rest? To be sure, there have been those who took the risk and opened their hearts to the path of contemplation. But rarely over those nearly 40 years was it ever more than a handful. Not so at L'Arche: my experience has been that those who attend liturgies want to go deeper. We are not dealing with fundamentals but the company of the committed so there is no need to persuade anyone. Nouwen amplifies my experience when he writes:

These words hit me with a thundering wallop! How long and hard have I worked to encourage people in my various congregations to trust God's grace rather than their shame over perceived holy judgment? How many different ways did I pitch the idea of finding 10 minutes - 5 minutes - even 1 minute each day to bask in the light of God's love? To seek out space for silent refreshment? To let go of doing long enough to rest? To be sure, there have been those who took the risk and opened their hearts to the path of contemplation. But rarely over those nearly 40 years was it ever more than a handful. Not so at L'Arche: my experience has been that those who attend liturgies want to go deeper. We are not dealing with fundamentals but the company of the committed so there is no need to persuade anyone. Nouwen amplifies my experience when he writes:

Here there is no urge to success; here time is filled with dressing,

feeding, carrying, and just being with those in need. It is a very demanding and tiring way, but there is no rivalry, no degree to be acquired, no honor to be desired - just faithful service. This is a new challenge for me. It requires me to develop the art of "spiritual companionship" with these fellow travelers. I now realize that the gospel of John was written for men and women like these. It was written for mature spiritual persons who do not want to argue about elementary issues, but who want to be introduced into the mysteries of the divine life.

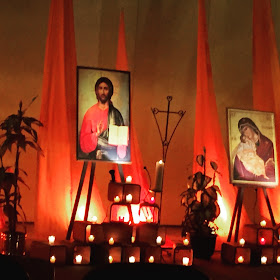

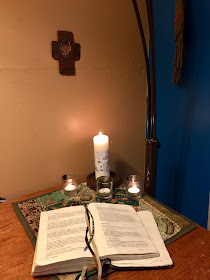

This is exactly what I have felt! In this context, authentic horizontal worship can take place organically. Indeed, when I celebrated Eucharist at L'Arche last week it was literally horizontal. On the floor. Just like Taize at its best. Small wonder that Jean Vanier has written a commentary on the Gospel of John and that I used it for the evening's gospel lesson.

The invitation in Scripture that night was to abide in God's love so that Christ's joy may be in us and our joy may be full. And that's what we talked about: experiencing Christ's joy, sharing this joy in acts of simple respect, opening our hearts to this joy even when we are apprehensive, and strengthening this joy in community.

Vanier calls the cultivation of Christ's joy within and among us "letting Jesus take up residence in our hearts." And he is clear that there is a connection between loneliness, love and joy: "To be lonely is to feel unwanted and unloved, and therefor unloveable. Loneliness is a taste of death. No wonder some people who are desperately lonely lose themselves in mental illness or violence to forget the inner pain." (Vanier, Becoming Human) Indeed, he understands that the fundamental calling of those who have chosen to let Jesus take up residence within their hearts is to encourage one another in the ordinary ways.

Each one of us is called to bridge the gap between the capable, rich person within us and the broken and fearful person who is also in us but whom we hide away. That means that those of us who have power, capacities, and wealth allow ourselves in small or big ways to be pruned, to be called from fear and egoism to love and truth, to share our lives with those who have no hope. The weak, the broken, on the other hand, are called to rise up, leaving their despair as they discover they are loved and respected. It is not always easy to accept hope and to receive help. (Vanier, Letter to My Brothers and Sisters)

This is exactly what I have felt! In this context, authentic horizontal worship can take place organically. Indeed, when I celebrated Eucharist at L'Arche last week it was literally horizontal. On the floor. Just like Taize at its best. Small wonder that Jean Vanier has written a commentary on the Gospel of John and that I used it for the evening's gospel lesson.

The invitation in Scripture that night was to abide in God's love so that Christ's joy may be in us and our joy may be full. And that's what we talked about: experiencing Christ's joy, sharing this joy in acts of simple respect, opening our hearts to this joy even when we are apprehensive, and strengthening this joy in community.

Vanier calls the cultivation of Christ's joy within and among us "letting Jesus take up residence in our hearts." And he is clear that there is a connection between loneliness, love and joy: "To be lonely is to feel unwanted and unloved, and therefor unloveable. Loneliness is a taste of death. No wonder some people who are desperately lonely lose themselves in mental illness or violence to forget the inner pain." (Vanier, Becoming Human) Indeed, he understands that the fundamental calling of those who have chosen to let Jesus take up residence within their hearts is to encourage one another in the ordinary ways.

Each one of us is called to bridge the gap between the capable, rich person within us and the broken and fearful person who is also in us but whom we hide away. That means that those of us who have power, capacities, and wealth allow ourselves in small or big ways to be pruned, to be called from fear and egoism to love and truth, to share our lives with those who have no hope. The weak, the broken, on the other hand, are called to rise up, leaving their despair as they discover they are loved and respected. It is not always easy to accept hope and to receive help. (Vanier, Letter to My Brothers and Sisters)

This, is what I have experienced. At this moment in my journey, it feels liberating to be at rest with those who do not need persuasion. Rather, our calling is to encourage, support and love one another right in the moment.