In my days as a pastor, I often discovered two surprises: 1) many of the faithful did not know how to pray; and 2) these same dedicated servants rarely, if ever, spoke about their inner experiences with the holy. At first I was bewildered: how could this be true - even while at church - that no one talked about God's love and how it had touched their hearts? It wasn't as if my friends hadn't encountered the presence of the sacred in their lives. They had - many times over. Still, they had been trained to keep such things to themselves. In silence.

In my days as a pastor, I often discovered two surprises: 1) many of the faithful did not know how to pray; and 2) these same dedicated servants rarely, if ever, spoke about their inner experiences with the holy. At first I was bewildered: how could this be true - even while at church - that no one talked about God's love and how it had touched their hearts? It wasn't as if my friends hadn't encountered the presence of the sacred in their lives. They had - many times over. Still, they had been trained to keep such things to themselves. In silence. So, while visiting in their homes, I took it upon myself to ask about the different ways they had experienced something of the Lord. And once given just a hint of encouragement, the stories came tumbling out. Eventually, we dedicated the first 20 minutes of every church meeting to listening to these stories. This led to a full year of reading, studying and discussing the way the Spirit of God had moved in our lives - and was moving in our congregation. We then put aside fretting about budgets, personnel, etc. at our administrative gatherings to listen for the still, small voice of the Lord in our midst. In time, we set out to teach one another how to pray, too: we explored quiet, contemplative prayer; structured and public liturgical prayer; using hymns as prayer prompts; and even extended times of quiet meditation.

In other words, we practiced spiritual formation. Once we owned that there was a gap in the maturation of our faith community, we could chart a course of correction. For just as there is a broad emotional and intellectual pattern for human development - see Erikson's nuanced and porous theory of psychosocial growth (https://www.simply psycholgy.org/Erik-Erikson. html) - so too are there stages of faith. Using Erikson's paradigm as well as the wisdom of Piaget and Kohlberg, James Fowler and others have suggested that faith development shares a comparable hierarchy of maturation. We start by mirroring what our families teach us, move into a season of mythical literalism, explore skepticism, etc. (https://www.uua.org/re/tapestry/youth/wholeness/workshop2/167602. shtml) To ripen beyond an adolescent rebellion or skepticism into a tender faith that honors doubt and ambiguity as well as grace and trust, requires training and encouragement.

In other words, we practiced spiritual formation. Once we owned that there was a gap in the maturation of our faith community, we could chart a course of correction. For just as there is a broad emotional and intellectual pattern for human development - see Erikson's nuanced and porous theory of psychosocial growth (https://www.simply psycholgy.org/Erik-Erikson. html) - so too are there stages of faith. Using Erikson's paradigm as well as the wisdom of Piaget and Kohlberg, James Fowler and others have suggested that faith development shares a comparable hierarchy of maturation. We start by mirroring what our families teach us, move into a season of mythical literalism, explore skepticism, etc. (https://www.uua.org/re/tapestry/youth/wholeness/workshop2/167602. shtml) To ripen beyond an adolescent rebellion or skepticism into a tender faith that honors doubt and ambiguity as well as grace and trust, requires training and encouragement.There are a host of resources, spiritual paths and ways to practice nourishing our spiritual lives: the Ennegram is one, the Rule of Benedict another; Buddhist meditation, Centering Prayer, Quaker silence and Sufi dance are still others. In Jean Vanier's small book, The Heart of L'Arche: a Spirituality for Every Day, the founder of the L'Arche movement shares yet another set of practices designed to help us grow in faith, ripen in mature love, and rest within the small but real presence of God in community. He summarizes the spiritual disciplines of L'Arche as a series of mysteries: the mysteries of Jesus, the mystery of the poor, the mystery of community, the mystery of a God who walks among us, and the mystery of the church. (NOTE: please see my previous posts re: the meaning of mystery @ https://rj-whenlovecomestotown.blogspot.com/ 2018/ 08/a-spirituality-of-larche-part-two.html)

Chapter two of Vanier's spirituality of L'Arche, "The mystery of the poor," is the longest. In it he shares both theological insights as well as practices to guide us in our journey into tenderness. After introducing the counter-cultural nature of this spirituality, I see four essential components of living into the mystery of the poor: 1) downward mobility; 2) a linkage of rich and poor; 3) personal vulnerability; and 4) trusting the hidden presence of God.

Chapter two of Vanier's spirituality of L'Arche, "The mystery of the poor," is the longest. In it he shares both theological insights as well as practices to guide us in our journey into tenderness. After introducing the counter-cultural nature of this spirituality, I see four essential components of living into the mystery of the poor: 1) downward mobility; 2) a linkage of rich and poor; 3) personal vulnerability; and 4) trusting the hidden presence of God.The mystery of the poor: "Over the years," Vanier writes, "I have come to realize the extent to which sharing our lives with people suffering from intellectual disabilities is counter-cultural. Soon after L'Arche began, I came across the passage in Luke's gospel in which Jesus says:

When you give a luncheon or dinner, do not invite your friends or your brothers and sisters or relatives or rich neighbors, in case they may invite you in return and you would be repaid. Rather, when you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind. And you will be blessed because they cannot repay..." (Luke 14: 12-14)

Here is the heart of L'Arche: a new form of family. "It is a way of life absolutely opposed to the values of a competitive, hierarchical society in which the weak are pushed aside." Vanier confesses that he had once thrived in that competitive world. "I wanted to be on top... and saw little value in those who were on the bottom." Only after succeeding in traditional ways - rising through the ranks of the navy, completing a Ph.D. and teaching at the university level - did he ask, "Is that all there is? Why is my heart still so empty? Isn't there a deeper meaning to my life?" The introduction to chapter two, "a spirituality centered on the mystery of the poor," puts it like this.

The two worlds that existed in the time of Jesus still exist today, in every country, city, town, and within every human heart. The rich are those who, believing they are self-sufficient, do not recognize their need for love and for others. They are the materially, culturally and even spiritually rich, who, self-satisfied, live in luxury, caught up in wealth, power and privilege. They have in abundance those things that fail to ever satisfy profoundly. Thus, ever in want, they constantly seek more, trapped in a vicious cycle of unrecognized dissatisfaction of the heart! Failing to recognize their own weakness, they look down on others, especially those who are different or weak. (p. 25)

He then notes that there are also countless people in our world who are marginalized. "They are the humiliated, living in poverty and misery... they are homeless, immigrants, unemployed, victims of abuse, the mentally ill, those who suffer with intellectual or physical disabilities, and the elderly who are lonely and neglected." The ministry of Jesus - and the mystery of the poor - is simple although upside down by traditional standards:

Jesus came to gather together in unity all the scattered children of God and give them fullness of life. He longs to put an end to hatred, to the preconceptions and fears that estrange individuals and groups. In this divided world he longs to create places of unity, reconciliation and peace, by inviting the rich to share and the poor to have hope. This is the mission of L'Arche... to dismantle the walls separating the weak from the strong, so that, together, they can recognize that they need each other and be united. This is the good news. (p. 26)

The four practices or spiritual disciplines of sharing the mystery of the poor are:

+ Downward mobility: This practice is an intentional opting-out of the race to win. Sometimes for a season, sometimes forever, individuals consciously choose to live into love rather than privilege. "Competitive, individualistic, materialistic societies detract from our humanity," Vanier notes. Small wonder that some parents have said, "It is such a waste that my son is in L'Arche; he could have done something really useful with his life." Modest stipends, shared meals, and life in community replaces the trajectory of traditional careers. "To live into this gift," Vanier continues, "we need spirit, an inspiration, and an inner force that urges us forward to grow in the love of all people in the human family." Like Jesus before us, some ask: "What does it profit a person to gain the whole world, but lose our soul?" (Matthew 16:26) The path of downward mobility is costly - it is the road less traveled - and often messy. At the same time there are glimpses of love, tons of laughter and tears, and a way of living that is rich in things not of this world.

To be a friend to the poor is demanding. They anchor us in the reality of pain; they make it impossible for us to escape into ideas or dreams. Their cry for solidarity obliges us to make choices: deepen our spiritual lives, put love and a sense of responsibility at the heart of our daily lives (rather than success.) This choice transforms us. (p. 32)

+ Unity of rich and poor: So much of our social organization is built upon utilitarianism: what can you do for me as quickly and as efficiently as possible? The commitment to linking rich and poor together demands a different relationship to time. Speed is no longer the prize. Utility is no longer the goal. Connecting in honesty supersedes everything else - a gift those of us who are rich must learn over and over again. For those who are poor live in the moment. Vanier writes: "I was once a man of action rather than a man who listened. In the navy I had colleagues, but no real friends. Opening ourselves to friendship means becoming vulnerable, taking off our masks and letting down our barriers so we can accept people just as they are, with all their beauty and gifts as well as all their weaknesses and inner wounds." When rich and poor embrace as equals formed in love we experience the blessings of heaven - if only for a moment. In this, rich and poor become united as solidarity reigns over competition - again, if only for a moment.

Loving involves letting others see my own poverty and giving them

space to love me... As I touched the fragility and pain of people with intellectual disabilities, and as their trust in me grew, new springs of tenderness welled up in me. I loved them and was happy with them. They awakened a part of my being that had been underdeveloped and dormant. Through them a new world began to open up for me, not the world of efficiency, competition, success and power, but the world of the heart, of vulnerability, communion and celebration. (p. 32)

+ Personal vulnerability: Tasting the promise of God's kingdom does not happen without a cost. Vanier interprets the spirituality of L'Arche through the lens of Christ's Cross: Jesus was not raised from death without suffering; nor was his resurrection on Easter Sunday possible without first wrestling with his conscience in the Garden, finding himself alone and abandoned as he faced the agony of the Cross, and trusting that God was greater than his emptiness. "If, at times, some people with disabilities awakened a new tenderness in me," he writes, "and it was a joy to be with them, at different moments others awakened my anger and my defensiveness.I was frightened that they might touch my vulnerability." Such is the paradox of this practice: to build trust and love with others demands coming fact to face with our own brokenness. Talk about counter-cultural! "It is hard to admit to the darkness, fears, anguish, confusion and psychological hatred in our own hearts, off of which hide our past hurts and reveal our inability to love." And until we face these wounds - and own them as real - the darkness will have more power than the light. Journaling, silent prayer, conversation with trusted friends,study and patience is part of how this practice strengthens love.

Faced with my anger and inability to love, I came into contact with my own humanity - and became more humble. I discovered that I was frightened of my own dark places, always wanting to succeed, to be admired and ready with the right answers. I was, however, hiding my poverty...(In time) I realized that to become a friend to people in need, I needed to pray and work on myself, with the help of the Holy spirit, and with good human and spiritual support - people who would walk with me and share my life. I had to learn to accept myself without any illusions... and little by little, the weak and the powerless helped me to accept my own poverty, become for fully human and grown in inner wholeness. (p. 34)

+ Trusting the hidden presence of God: Vanier believes that the weak are God's chosen people. They know when they are loved. They know when they are rejected. Or forgotten. Or marginalized. "When children know that they are loved, they are peaceful. When they feel unwanted, they are in pain. They learn through contact with their hearts, their bodies and their senses." This is one of the gifts people with intellectual disabilities - God's chosen - can share with the world: living from the heart and body. This is a hidden gift. This is the presence of God that many cannot grasp. St. Paul put it like this in his counter-cultural confession: "God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world..." to show us all the way into love. (I Corinthians 1:27-28) Some in the ancient monastic movements of early Christianity spoke of this as being "fools for Christ." It is a way of trusting that God's hidden presence guides and shapes all of creation. "The mystery is that our God is a hidden God."

Our God is not a God of rules, regulations and obligations, or a master teacher who wants to impose a path of salvation. Our God is a God of love and communion, a heart yearning to communicate to another heart the joy and ecstasy of love and communion that exist between the Father, Son and Holy Spirit... (Small wonder then that) God who is all powerful, all beautiful, all glorious becomes powerless, little and weak. The logic of love is different form the logic or reason and power. When you love someone, you use her language to be close to her. When you love a child, you speak and play with him as a child. That is how God relates to us. God becomes little - hidden - so that we will not be frightened. so that we can enter into a heart-to-hear relationship of love and communion. (p. 42)

The mystery of the poor is costly. It is hard for all involved - not just ourselves. It inverts the way we think the world works - a realm of busyness, efficiency and usefulness - for a life of listening, welcoming and sharing. Vanier confesses that the "poor lead us all from selfishness into generosity and then compassion." It is much like the meeting of Jesus and Peter after the betrayal of Good Friday and the shock of Easter Sunday. Peter has run away in disgrace. He had turned his back on Jesus after promising to love him forever. Peter has returned to his life as a fishermen. This happens in our lives too after failing or disappointing those we love: we go back to our old habits. After working all night with no success, Jesus appears to Peter on the beach. Peter, however, is still heart broken and cannot yet recognize the one he loves so he ignores the quiet presence of Jesus.

Jesus asks him to give fishing one more try. And after an argument, Peter agrees and takes in a great catch of fish. Then his eyes are opened and they eat an Easter breakfast together on the beach. Before Jesus moves on, however, he asks Peter three times: "Do you love me?" One for each betrayal. Peter is filled with sorrow and shame as Jesus helps Peter own the cost of his emptiness and fear. Peter needs to know the truth about his humanity. Then, Jesus tells Peter that "When you were young, you went wherever you wanted. But now that you are older, another will have to give you support and will lead you into those place you do not want to go." (John 21) The mystery of the poor leads us all - rich and poor - into quiet tenderness. It is a costly transformation much like the Cross that reorders the totality of our existence.

credits:

+ Old prayer book: jlumsden

+ Erikson chart: google

+ Harry's art: jlumsden

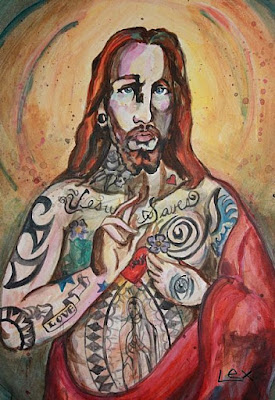

+ Contemporary Jesus: https://www.pinterest.com/lespinola02/contemporary-art-of-jesus/

+ Heart of love: google

+ Montreal Ice: jlumsden

+ Communion chalice

+ Jesus and Peter: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/403635185335192991/

No comments:

Post a Comment